Figp1.03.png

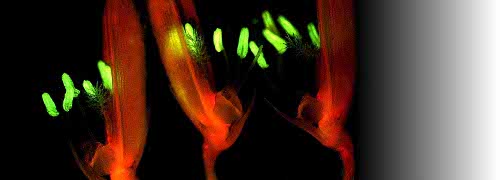

Figure 1.3 Light absorption by pigments in solution and by leaves. Absorbance (A) refers to attenuation of light transmitted through a leaf or a solution of leaf pigments, as measured in a spectrophotometer, and is derived from the expression A = log I0/I where I0 is incident light, and I is transmitted light. The solid curve (scale on right ordinate) shows absorbance of a solution of pigment—protein complexes equivalent to that of a leaf with 0.5 mmol Chl m-2. The dotted curve shows absorptance (scale on left ordinate), and represents the fraction of light entering the solution that is absorbed. Virtually all light between 400 and 500 nm and around 675 nm is absorbed, compared with only 40% of light around 550 nm (green). The dashed curve with squares represents leaf absorptance, which does not reach 1 because the leaf surface reflects part of the incident light. Leaves absorb more light around 550 nm than a solution with the same amount of pigment (75 versus 38%, respectively) because leaves scatter light internally. This increases the pathlength and thereby increases the probability of absorption above that observed for the same pigment concentration in solution. (Based on K.J. McCree, Agric Meteorol 9: 191-216, 1972; J.R. Evans and J.M. Anderson, BBA 892: 75-82, 1987)

Pigments in thylakoid membranes of individual chloroplasts (Figure 1.7) are ultimately responsible for strong absorption of wavelengths corresponding to blue and red regions of the visible spectrum (Figure 1.3). Irradiated with red or blue light, leaves appear dark due to this strong absorption, but in white light leaves appear green due to weak absorption around 550 nm, which corresponds to green light. Ultraviolet (UV) light (wavelengths below 400 nm) can be damaging to macromolecules, and sensitive photosynthetic membranes also suffer. Consequently, plants adapt by developing an effective sunscreen in their cuticular and epidermal layers.

Overall, absorption of visible light by mesophyll tissue is complex due to sieve-effects and scattering. Sieve-effect is an outcome from packaging pigments into discrete units, in this case chloroplasts, while remaining leaf tissue is transparent. This increases the probability that light can bypass some pigment and penetrate more deeply. A regular, parallel arrangement of columnar cells in the palisade tissue with chloroplasts all vertically aligned means that about 80% of light entering a leaf initially bypasses the chloroplasts, and measurements of absorption in a light integrating sphere confirm this. Scattering occurs by reflection and refraction of light at cell walls due to the different refractive indices of air and water. Irregular-shaped cells in spongy tissues enhance scattering, increasing the path length of light travelling through a leaf and thus increasing the probability of absorption. Path lengthening is particularly important for those wavelengths more weakly absorbed and results in nearly 80% absorption, even at 550 nm (Figure 1.3). Consequently, leaves typically absorb about 85% of incident light between 400 and 700 nm; only about 10% is reflected and the remaining 5% is transmitted. These percentages do of course vary according to genotype × environment factors, and especially adaptation to aridity and light climate.

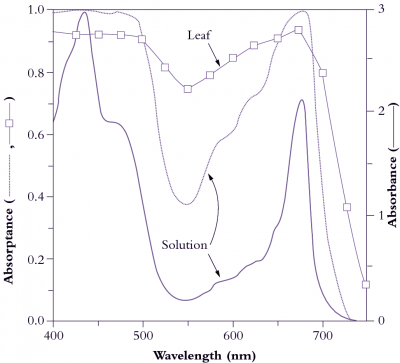

Sunlight entering leaves is attenuated with depth in much the same way as light entering a canopy of leaves shows a logarithmic attenuation with depth that follows Beer’s Law (Section 12.4). Within individual leaves, the pattern of light absorption is a function of both cell anatomy and distribution of pigments. An example of several spatial profiles for a spinach leaf is shown in Figure 1.4. Chlorophyll density peaks in the lower palisade layer and decreases towards each surface. The amount of light declines roughly exponentially with increasing depth through the leaf. Light absorption is then given by the product of the chlorophyll and light profiles. Light absorption initially increases from the upper surface, peaking near the base of the first palisade layer, then declines steadily towards the lower surface. Because light is the pre-eminent driving variable for photosynthesis, CO2 fixation tends to follow the light absorption profile (see 14C fixation pattern in Figure 1.4). However, the profile is skewed towards the lower surface because of a non-uniform distribution of photosynthetic capacity. Chloroplasts near the upper surface have ‘sun’-type characteristics which include a higher ratio of Rubisco to chlorophyll and higher rate of electron transport per unit chlorophyll. Chloroplasts near the lower surface show the converse features of ‘shade’ chloroplasts. Similar differences between ‘sun’ and ‘shade’ leaves are also apparent. Chloroplast properties do not change as much as the rate of absorption of light. Consequently, the amount of CO2 fixed per quanta absorbed increases with increasing depth beneath the upper leaf surface. The lower half of a leaf absorbs about 25% of incoming light, but is responsible for about 31% of a leaf’s total CO2 assimilation.

Figp1.04.png

Figure 1.4 Profiles of chlorophyll, light absorption and photosynthetic activity through a spinach leaf. Cell outlines are shown in transverse section (left side). Triangles represent the fraction of total leaf chlorophyll in each layer. The light profile (dotted curve) can then be calculated from the Beer—Lambert law. The profile of absorbed light is thus the product of the chlorophyll and light profiles (solid curve). CO2 fixation, revealed by 14C labelling, follows the absorbed light profile, being skewed towards slightly greater depths. (Based on J.N. Nishio et al., Plant Cell 5: 953-961, 1993; J.R. Evans, Aust J Plant Physiol 22: 865-873, 1995)