Abdelbagi M. Ismail, International Rice Research Institute, The Philippines

The genus Oryza constitutes about 24 species, 20 of which are wild and only O. sativa and O. glaberrima are cultivated. O. sativa is grown worldwide, whereas O. glaberrima is restricted mostly to West Africa. Ecological and geographic distribution of these species is largely determined by temperature and water availability. O. sativa is cultivated on about 144 million ha worldwide, from 50° N in North China to 35° S in Australia (New South Wales) and in Argentina. It is also grown from 3 m below sea level in Kerala, India, to as high as 3000 m in Nepal and Bhutan. Two broad categories are generally identified within O. sativa, with some overlaps; japonica varieties are mostly grown in temperate regions, while indica varieties are grown in tropical and subtropical areas. A third category― tropical-japonica ― is mostly grown in the uplands of the tropics and subtropics. Japonica types are known for their better tolerance of low temperatures compared with indica types, and japonica types also have shorter, thicker grains that are softer and stickier when cooked.

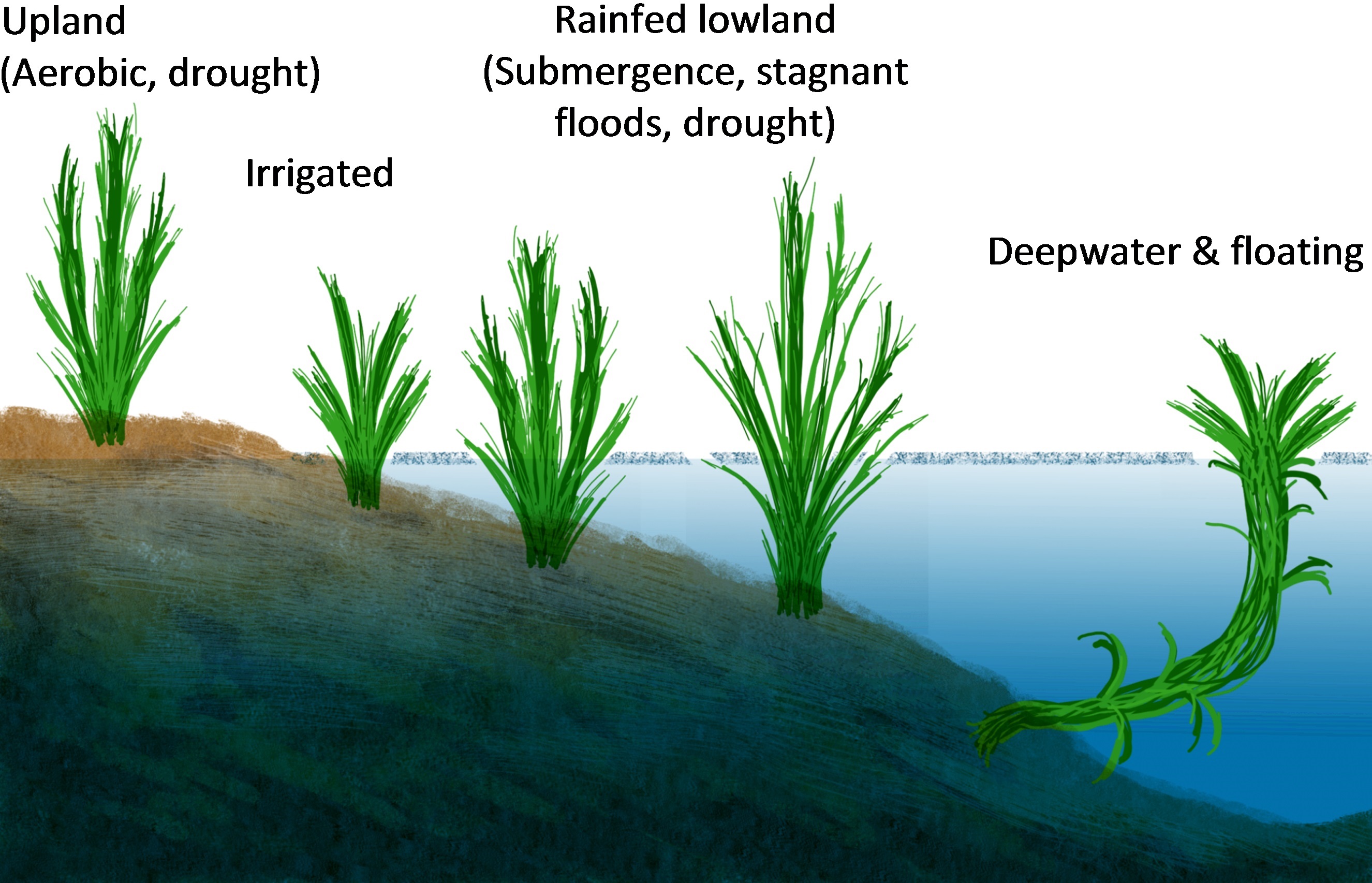

Rice is grown on a variety of soils, but the physical ability of the soil to hold water is an important property, so medium- and heavier-textured soils are typically favoured over light-textured sandy soils. It is also grown under variable water regimes and hydrological conditions, from aerobic soils as in uplands, to flooded soils in irrigated and rainfed lowlands, to long-duration flooded conditions in flood-prone areas (Figure 1).

CS_18.1-2.jpg

Figure 2. Rice terraces of Madagascar. A typical example where rice is grown under different ecologies, from uplands at the top of the slope, to more favourable rainfed and irrigated areas midway, to flood prone areas at the bottom of the slope. Farmers normally grow different varieties based on adaptation to each condition. (Photograph courtesy A. M. Ismail)

The enormous plasticity in rice to adapt to these diverse ecologies led to the development of substantial numbers of rice cultivars with diverse morphology, phenology and other adaptive and grain characteristics. The Genetic Resource Center of the International Rice Research Institute hosts over 117,000 accessions collected worldwide (http://irri.org/our-work/research/genetic-diversity/international-rice-genebank).

This peculiar diversity within Oryza species made rice one of the most widely grown crops over an extreme range of habitats, and a spectacular model for plant ecophysiological and genetic studies. Various types of models were used to classify rice types based on field ecologies. The most widely used classification distinguishes four broad categories; upland, irrigated lowland, rainfed lowland and flood-prone ecosystems (Maclean et al., 2002). Characters of varieties suitable for each ecology are mostly determined by local hydrology, and in some cases multiple systems co-exist based on the toposequence (Figure 2).

Upland rice is grown in aerobic unbunded soils with topographies ranging from undulating and steep sloping lands with high runoff, to low-laying valleys and well-drained flat lands. Soils vary considerably in texture, fertility and water holding capacity; from poor highly leached soils of West Africa, to fertile soils in Southeast Asia. About 13% of the world rice is grown in uplands, but with low yields of about 1 t ha-1, and farmers are among the poorest. Upland varieties are mostly short maturing, with deeper roots (drought avoidance) and with higher tolerance of acid soils.

Irrigated ecosystem is the largest rice production system, covering 55% of the world rice area and producing over 75% of world rice grains. Fields have assured water supply and rice is grown in puddled soil in bunded fields with water depths of 2.5-10 cm through most of the season, and with 1-3 crops per year depending on location and farming systems. Dwarf high yielding varieties that are responsive to high use of fertilizers are predominant, and yields are usually high, averaging over 5 t ha-1.

Rainfed lowlands constitute about one quarter of rice world lands and contribute about 18% of rice production. These areas are generally densely populated with poor communities, and are prone to both drought and submergence because of lack of water control, besides adverse soils, inhibiting adoption of high-yielding varieties and use of high-cost fertilizer inputs. Local landraces with yields of less than 2 t ha-1 still dominate in most areas; however, new high-yielding varieties tolerant of prevailing abiotic factors are becoming available over recent years and are gradually replacing existing local landraces.

Flood-prone rice ecosystems are subjected to uncontrolled floods, ranging from transient flash-floods causing complete submergence, to longer term floods of 0.5 m to over 4.0 m for most of the season, and sometimes associated with excess salinity, acid sulfates and drought. Over 15 million ha in South and Southeast Asia are annually affected by uncontrolled floods. Yields are low, averaging 1.5 t ha-1, and yet these areas support over 100 million people. Traditional varieties still dominate because they are better adapted to water fluctuations than modern varieties. Recently, varieties that tolerate complete submergence are becoming available through the incorporation of the SUB1A gene (see also main text). These varieties tolerate 1-2 weeks of complete submergence and considerable yield benefits have been achieved in farmers’ fields, with yield advantages of 1 to over 3 t ha-1 (Mackill et al., 2012).

The extreme diversity in adaptation to various ecological and hydraulic conditions made rice one of the most widely grown cereal crops worldwide; and an interesting model for crop improvement research. Currently, rice is the most important food crop in developing word and the stable food for over half of the world population.

Further reading on this topic:

Maclean JL, Dawe DC, Hardy B, Hettel GP (2002) Rice Almanac. Los Banos (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute, pp 16-24 http://books.irri.org/0851996361_content.pdf

Mackill DJ, Ismail AM, Singh US, Labios RV, Paris TR (2012) Development and rapid adoption of submergence-tolerant (Sub1) rice varieties. Adv Agron 115: 303-356.