A rapidly transpiring leaf can evaporate its own fresh weight of water in 10 to 20 min, though many plants such as cacti, mangroves and plants in deep shade have much smaller rates of water turnover. Leaf veins must carry this water to all parts of a leaf to replace evaporated water, and maintain cell hydration and turgor. When water supply fails to meet this demand, shoots wilt.

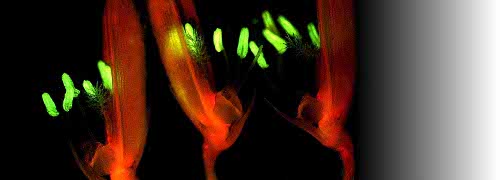

3.0-Ch-Fig-3.20.jpg

Figure 3.20 Typical leaf vein pattern of broad-leaf species versus grasses. Left: Leaf of Eucalyptus crenulata showing the arrangement of supply and distribution veins. Large veins with large vessels, in which water is moved rapidly across the lamina, surround islets of small veins with small vessels in which water is slowly distributed locally. Scale bar, 1 mm. Right: Leaf of wheat (Triticum aestivum) showing one large and three small longitudinal veins, with transverse veins connecting them. Scale bar, 0.1 mm. Distance between small veins is about 0.15 mm in both species. (Photographs courtesy of M. McCully and M. Canny)

Vein distribution patterns differ markedly between broad-leaf species and grasses. Broad-leaf species generally have a highly branched network while grass species have parallel veins (Figure 3.20).

Veins consist typically of tightly packed xylem and phloem tissues surrounded by a parenchymatous or fibrous sheath. Both xylem and the phloem contain living parenchyma cells as well as their characteristic transporting conduits: vessels and/or tracheids in the xylem tissue, plus sieve tubes in the phloem tissue. There are no intercellular air-spaces, or only very small ones.

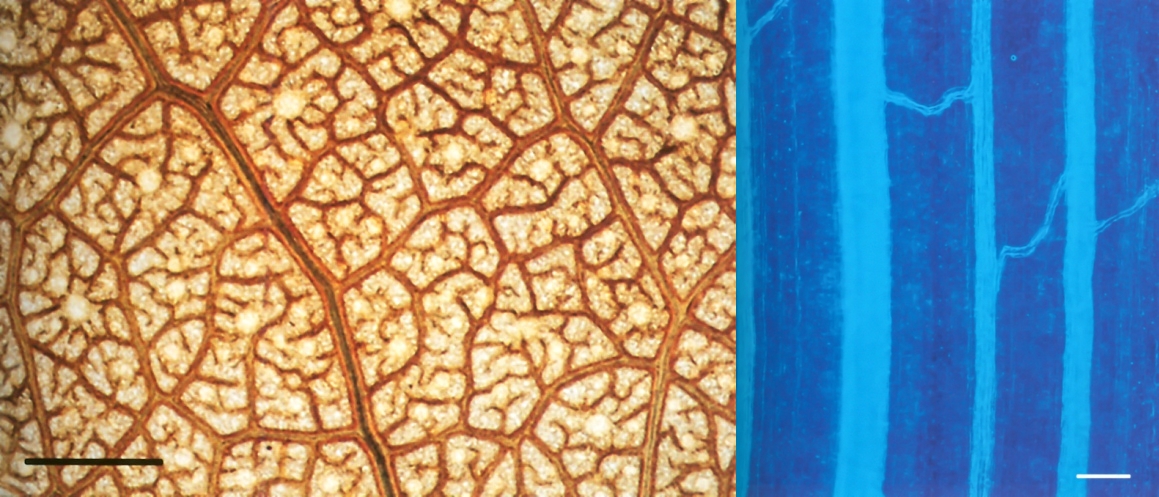

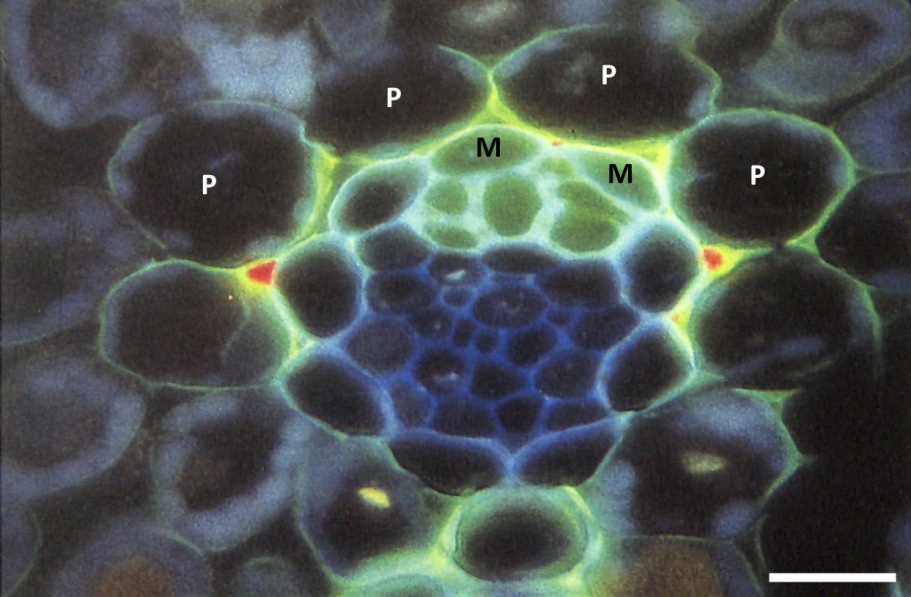

3.0-Ch-Fig-3.21.jpeg

Figure 3.21 Transverse section of small intermediate vein of wheat leaf, after being fed the fluorochrome sulphorodamine, which acts as a tracer for water movement. Water passes out of the xylem through paths in the walls of the mestome sheath cells (M) and enters the parenchymatous sheath cells (P) leaving red crystals in the intercellular spaces. Scale bar, 15 µm. Image, M. Canny. (Reproduced from New Phytologist, Tansley Review No 22, 1990)

The ring of cells forming the sheath around the xylem and phloem tissue acts both as a mechanical barrier that may confine pressure within the vein, and a permeability barrier that can control rates and places of entry and exit of materials (Figure 3.21).